After retirement

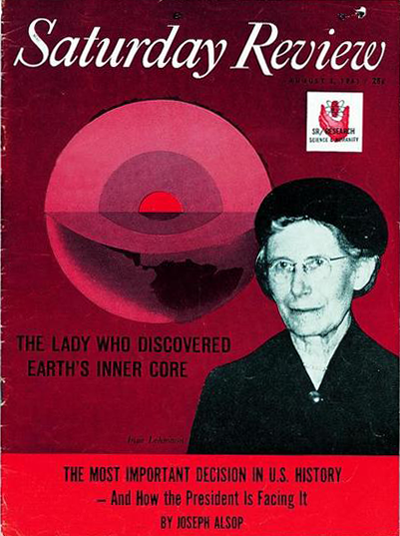

After her retirement in 1953, Inge Lehmann looks abroad and especially towards the United States and begins to take an interest in studies of the Earth’s mantle based on nuclear testing. And recognition comes rolling in with numerous international awards.

After she retires in 1953, Inge Lehmann almost becomes more active and she begins to visit the United States and Canada regularly and works at the most famous research institutes in the world.

Here she gets the chance to process signals from subterranean nuclear testing and to make computations on newly developed electronic calculators.

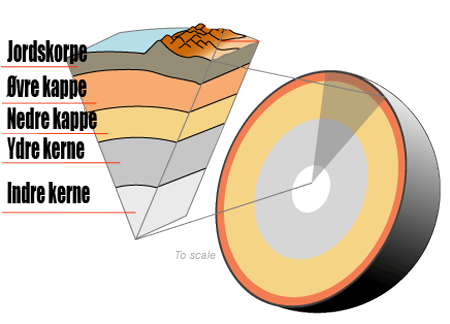

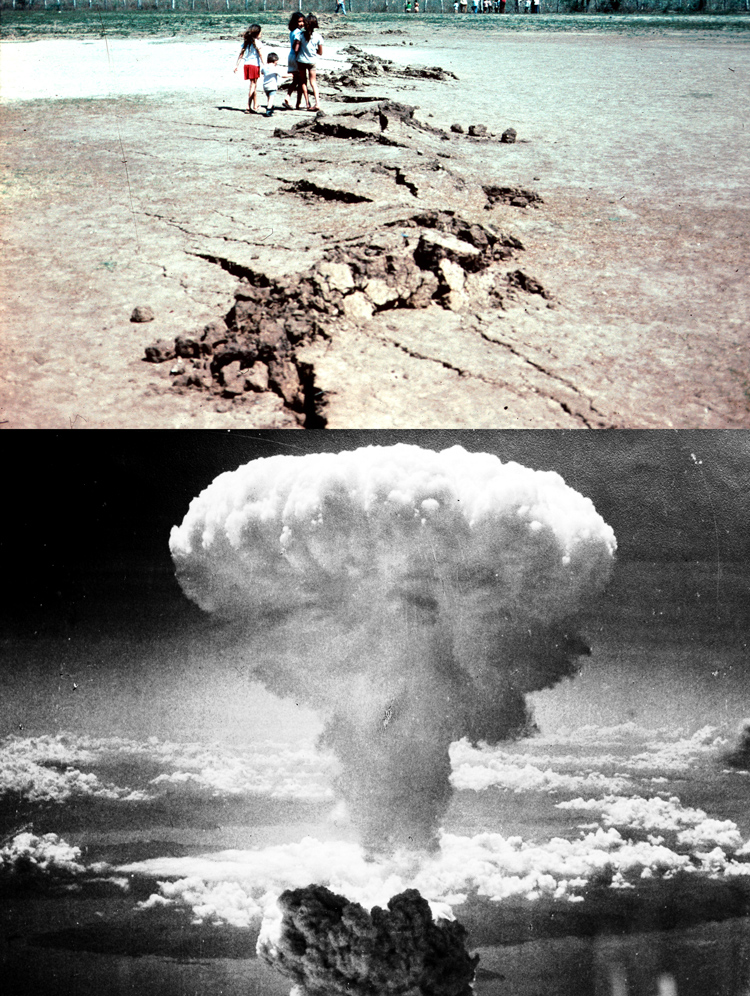

In 1960, there is an earthquake in Chile that kills 5700 people and is so powerful that it offers new seismic data about the Earth’s interior. In combination with analyses of other earthquakes, this confirms Inge Lehmann’s hypothesis about the Earth’s inner core, which now goes from being a theory to a universally accepted fact.

This also means that Inge Lehmann’s fame increases and it really begins to dawn on the scientific community how important the modest article P' from 1936 was.

The ‘Lehmann discontinuity’

Up through the 1960s, she receives a torrent of international honours, but they still do not pay her much notice in her native Denmark.

After her retirement she moves away from working with the Earth’s core and instead begins to study the Earth’s upper mantle.

In the beginning, she primarily looks at North American earthquakes, but the Cold War also has its advantages and it gradually becomes possible for her to rely on nuclear testing instead.

She discovers, for example, a so-called ‘discontinuity’ in the study of the P-waves at a depth of about 220 kilometers. This later becomes known as the ‘Lehmann discontinuity’.

In 1956, she writes the article Danish Earthquakes, where she gathers the information available on all Danish earthquakes since the year 1073.

Finally a gold medal

In January 1962, her good friend, the geophysicist Harold Jeffreys, writes to Niels Bohr and expresses his surprise that Inge Lehmann has not received honours in her own country, after which he encourages Bohr to do something about it.

Niels Bohr apparently finds the request reasonable, as he writes to Niels E. Nørlund from the Geodetic Institute, where Inge Lehmann worked for many years, and Nørlund suggest that Lehmann be recommended for the Gold Medal of the Royal Danish Academy of Science and Letters. She receives it in 1965 – but as mentioned above, it was at urging from abroad.

She also continues to collaborate with Dr. Maurice Ewing from the Lamont Geological Observatory to study the tremors from nuclear explosions and he later says of her:

“Her work with nuclear test blasts was important, not so much because she discovered something new, but because her stature and her integrity gave respectability and credibility to those whose studies she showed an interest in.”

An invaluable resource

The atmosphere cannot help but be somewhat political, but Inge Lehmann is unassailable:

“This was not an insignificant point in the somewhat political – as opposed to a purely scientific – atmosphere in a time where nuclear testing was a hot political topic. Less well-known seismologists could be suspected of supporting a particular political point of view,” explains Maurice Ewing.

Bruce Bolt, a professor of seismology at the University of California, Berkeley, later argues that the Americans in the 1960s consider Inge Lehmann to be an invaluable resource – including for the development of highly specialised and standardised seismographs around the world.

No one can measure up to her, they think…

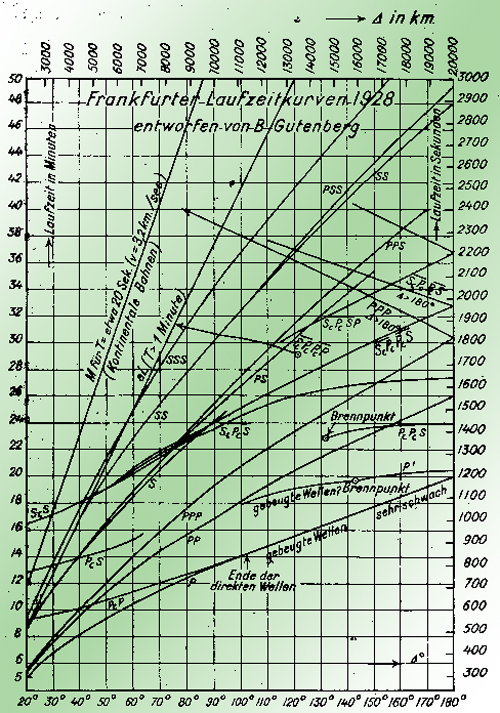

Here is a diagram of various seismic wave sequences taken from Inge Lehmann’s last article, Seismology in the Days of Old, which she published as a 99-year-old in 1987.

Tremors in the Earth

When Inge Lehmann published the groundbreaking article P' in 1936, her results about the Earth’s solid core were based on measurements of a specific earthquake in New Zealand in 1929.

When she starts to take an interest in the Earth’s upper mantle after her retirement in the 1960s, it is based on nuclear testing and measurements of the resulting seismic waves.