Inge Lehmann and the interior of the Earth

Inge Lehmann (1888-1993) was the woman who in 1936, based on innovative readings of seismological measurements, argued that the Earth must have a solid inner core. This set her in opposition to contemporary expert opinions, but it soon became apparent that she was right and she could reap her well-deserved recognition. But in Denmark, she is still unknown.

Denmark’s leading Mars researcher, geophysicist Jens Martin Knudsen (1930-2005), often referred to Inge Lehmann as one of the country’s best scientists along with Tycho Brahe, Ole Rømer, H.C. Ørsted and Niels Bohr, yet there are very few who have heard about her today.

With Bjarne Kousholt’s biography, Inge Lehmann and the Earth’s core (2005), as a notable exception, very few articles and books have been published about this great Danish woman.

Misunderstood genius in Denmark

But abroad, and particularly in the United States, it is different. Especially after her retirement, Inge Lehmann collaborates with some the greatest seismologists and other geophysicists of the time, including Beno Gutenberg, Harold Jeffreys and Maurice Ewing, later called her “American gang” in Weekendavisen (The Weekend Newspaper).

Inge Lehmann became famous throughout the world because she is the first to discover that the Earth’s core is not liquid as was previously thought, but instead is comprised of a relatively solid material.

She discovers this through her unique analysis of seismograms and her method is later described as “black magic, which no computer can imitate.”

An intelligent and sickly child

Inge Lehmann was born in 1888 – the year after her parents were married. She gets a little sister, Harriet, who later becomes an actress and throughout her childhood the family lives on Kastelsvej in Østerbro in Copenhagen.

Inge Lehmann is an exceptionally gifted and inquisitive person and even as a child she had a proclivity towards knowledge, which her parents also had to acknowledge when they discover the 11-year-old Inge with some older boys after a school ball – hard at work solving quadratic equations.

But the little Inge is also a sickly child and when a dedicated math teacher tries to challenge her by giving her extra assignments, her parents protest because they are afraid that she would overexert herself with all of her studies.

“One could not expect them to understand that I could have been stronger if I had not been so bored in school,” wrote Inge Lehmann later about her parents.

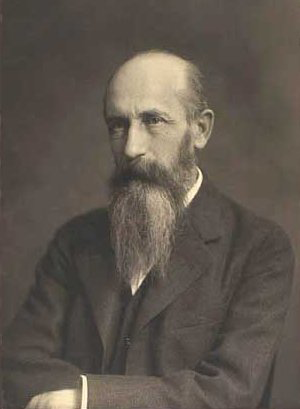

Her father, the famous psychologist Alfred Lehmann, was that man who introduced the so-called ‘experimental psychology’ to Denmark and he was appointed professor of psychology at the University of Copenhagen in 1919.

On the right track

He is Inge’s role model and he prefers to work with the ‘exact sciences’ – also in his psychological studies.

He writes, for example, the book an Superstition and Witchcraft, which takes a critical look at the popular fads in spiritualism and other so-called ‘supernatural’ phenomena and it was most recently republished by Thaning & Appel in 1999.

Alfred Lehmann firmly believes that it is possible to identify all human strengths and weaknesses and thus place them on the right track – a mindset that you also find in today’s personality tests, which are used to place people in an organization or in a business in accordance with their personality.

Inge describes her father as a very industrious person who was rarely at home with his family and it is clear that she admires his dedication to his profession.

No difference between boys and girls

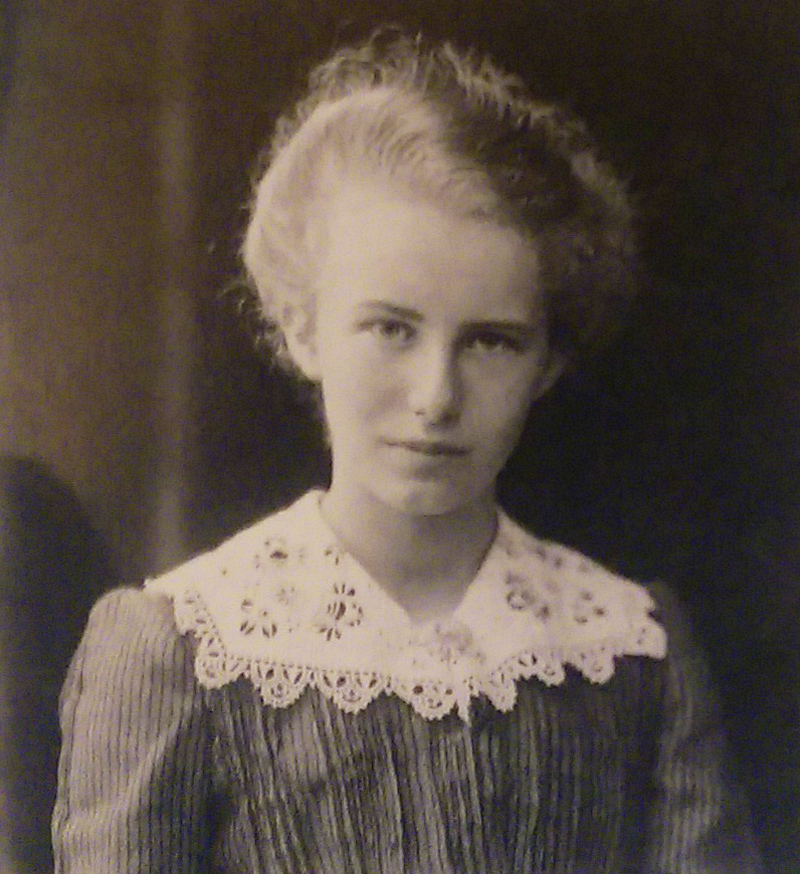

Inge Lehmann attends ‘H. Adler’s Co-educational School’. The H stands for Hanna and she is the charismatic headmistress of the school which, following the American model, treats students as individuals and does not discriminate between girls and boys.

The boys participate in cooking and sewing on an equal footing with the girls, who in turn play enthusiastically in the football matches.

Many years later – in 1947 - Inge Lehmann writes the obituary for Hanna Adler and it is clear from the empathetic text that the progressive, female head teacher had been a great inspiration for the budding scientist.

Fresh air in the school

”In retrospect, we know that there was an unusual amount fresh air in the school – not just because of the open windows and breaks every half hour. There was no undue coercion and we escaped being saddled with the prejudices with which people make life difficult for each other. We grew up boys and girls together, roughly in equal numbers. We were a motley crew, individually different; but the distinctions of gender, race or social conditions did not exist for us,” writes Inge Lehmann in the obituary.

"We were a motley crew, individually different; but the distinctions of gender, race or social conditions did not exist for us ...

Inge Lehmann in 1947, about her time at Hanna Adler's Co-educational School

Later in life, however, she says that it had also given rise to disappointment for her when she got older, including as a student at Cambridge University, where the female students were subject to stricter rules than their male counterparts:

“No difference between boys’ and girls’ intellect was recognised [at H. Adler’s Co-educational School], a fact that gave some disappointment later in life when I had to realise that this was not the popular opinion,” she explains.

In 1943, during World War II, the 84-year-old Hanna Adler, who is a Jew, is interned in Horserød camp. This causes 400 of her former students from the Co-educational School, including Inge Lehmann, to write to the German Plenipotentiary in Denmark, Werner Best, to persuade him to release her again.

They succeed and she dies in freedom a few years later

Hanna Adler (1859-1947) was headmistress of the progressive school H. Adler’s Co-educational School in Østebro in Copenhagen, which, following the American model, did not discriminate between boys and girls.

In 1892, she and Kirstine Meyer were the first women to receive MSc degrees in physics at the University of Copenhagen. She was also the sister of Niels Bohr’s mother.

Recently returned from a study trip to the United States, the purpose of which was to study conditions in American schools, where girls and boys were taught together, she established the first co-educational school in Denmark in 1893.

Free and Friendly

She succeeded in creating a school that was characterised by a free, friendly and equal relationship between teachers and students and between the students themselves and she implemented co-education in all areas, even gymnastics, sewing and cooking.

The school, which was taken over by the state in 1918, was led by Hanna Adler until 1929, but it would be another 16 years before co-education with boys and girls together was introduced as general principle in Copenhagen in 1946.

Seen below is the school as it is today, now called the Sortedam School.