'P' eller opdagelsen af Jordens kerne

Inge Lehmann really makes a name for herself internationally with the article P', published in 1936. In it she argues that some strange vibration signals from an earthquake in New Zealand can only be explained if one assumes that the Earth has a solid inner core. This is unprecedented and the thought creates debate among the world’s seismologists.

The new seismological stations Inge Lehmann has helped install for the Geodetic Institute in Denmark and Greenland are located far from the Earth’s major earthquake zones – often in the so-called ‘shadow area’.

This is unusual and provides Inge Lehmann with new information, as she has the opportunity to analyse the seismograms coming in.

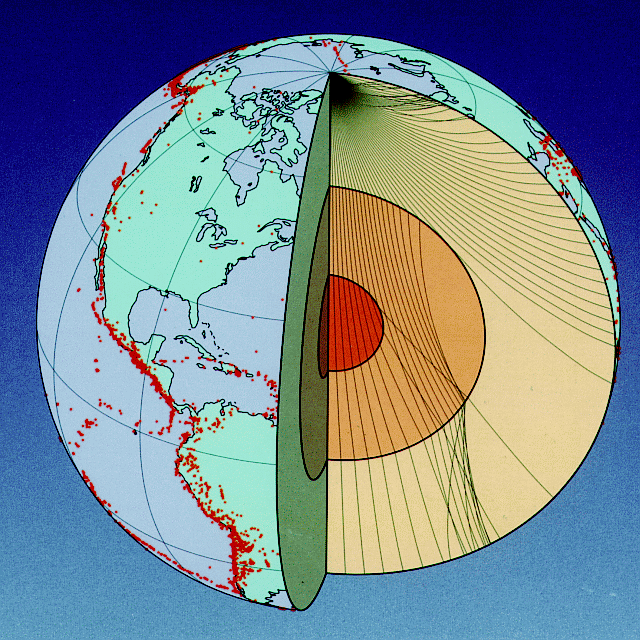

In the 1930s, they believe that the Earth is comprised of two layers. A liquid core and a solid mantle.

A groundbreaking discovery

But the seismographic waves also show an abnormality, which cannot immediately be explained and then Inge Lehmann develops her theory of a solid core in the Earth’s interior.

She does so using measurements of a New Zealand earthquake in 1929.

Using her creative brain, the Danish Inge Lehmann is thus one of the first to figure out that the Earth has a solid inner core – the other seismologists of the period only have fumbling explanations of the P-wave refraction.

P’ is published in 1936 and Inge Lehmann concludes modestly with the words:

“It cannot be maintained that the interpretation here given is correct since that data are quite insufficient and complications arise from the fact that small shocks have occurred immediately before the main shock.”

“However, the interpretation seems possible, and the assumption of the existence of an inner core is, at least, not contradicted by the observations; these are, perhaps, more easily explained on this assumption,” she writes and continues:

"I hope that the suggestions her made may be considered by other investigators ...

Inge Lehmann, P', 1936

“I hope that the suggestions made here may be considered by other investigators, and that suitable material may be found for studies of the P’ curves.”

“The question of the existence of the inner core cannot however be regarded solely from a seismological point of view, but must be considered also in its other geophysical aspects,” she concludes.

From scepticism to acceptance

Beno Gutenberg immediately approves of the conclusion, while her other good research friend, Harold Jeffreys, hesitates a bit longer.

In 1938, Beno Gutenberg and his colleague Charles Francis Richter discover that the Earth’s inner core must have a radius of about 1,200 kilometers.Within a few years, however, he has himself proven that the old theories cannot explain the concrete observations and then he also accepts the idea that the Earth has a solid inner core.

At the same time, they determine that the so-called P-waves that Inge Lehmann had also studied, are traveling at a speed of 11.2 kilometers per second on their journey through the Earth’s inner core.

Not many years pass before Inge Lehmann’s hypothesis becomes widely accepted among other scientists, but it is not until almost 25 years later that studies of a massive earthquake in Chile finally confirm the existence of Inge Lehmann’s inner core.

"A master of a black art"

Inge Lehmann’s article P' causes a stir among seismologists and other geophysicists around the world for its conclusions about the Earth’s inner core. But Lehmann herself is primarily famous for her method of reading the seismograms.

"... a master of black art for which no amount of computerization is likely to be a complete substitute...

Geophysicist Francis Birch about Inge Lehmann in 1971

When Inge Lehmann is finally recognized as the discoverer of the Earth’s inner core many years later and receives the so-called Bowie Medal (which is the highest honour of the American Geophysical Union), her abilities are referred to as pure magic by her colleagues:

"The Lehmann discontinuity was discovered through in-depth studies of seismic recordings by a master of a black art for which no amount of computerization is likely to be a complete substitute…” says professor Francis Birch at the presentation.

In 1936, she is also the co-founder of the Danish Geophysical Union, which she also serves as chairman of from 1941–1944.

Jordens indre kerne er Jordens inderste del og består af en fast kugle med en radius på omkring 1220 kilometer. Man anslår, at kernen primært består af jern og nikkel, og at den er omkring samme temperatur som Solen, nemlig 5400 grader celcius.

Inden Inge Lehmanns artikel P', der udkom i 1936, og som beviste eksistensen af en fast, indre kerne, var den almindelige holdning blandt eksperter, at Jordens indre var helt flydende.

Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1864) by Jules Verne finds a small group of scientists and adventurers heading into the Earth, where they discover living dinosaurs and a great sea, before they finally find their way back to the surface through the Stromboli volcano in southern Italy.

But this is not the first time man has fantasised about a new world inside the Earth, like the English astronomer Edmund Halley, who in an article in 1694 suggested that the Earth was comprised of several hollow spheres within each other and that the internal planets might be inhabited.

The idea of a kind of underworld was also found in many places in ancient mythology and also in Christianity, where Dante Alghieri’s The Divine Comedy from the 14th century and John Milton’s Paradise Lost from 1667 helped shape the idea of a subterranean hell.

Today, the idea of the hollow Earth is only held by the most die-hard conspiracy theorists, such as ‘Doctor’ Walter Siegmeister, who, in his book Hollow Earth from 1964, explains the mystery of both UFOs and Atlantis based on the theory of a hollow, inhabited interior world.

Seen below is one of Édouard Rious illustrations for Jules Verne’s science fiction classic Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1864).