Hafnium

In the parlance of physics at the time, as well as in Bohr's mind, the word ‘theoretical' in the institute's name did not mean that it was removed from experimental research. Quite on the contrary, one of Bohr's main motivations for establishing an institute was exactly the opportunity it gave for conducting experiments, his vision being that the theoreticians needed to have their ideas tested on site.

From the beginning, therefore, people working at the institute included experimental physicists, and elaborate spectroscopical equipment was installed to test the theoreticians' predictions of atomic physics.

From the beginning, therefore, people working at the institute included experimental physicists, and elaborate spectroscopical equipment was installed to test the theoreticians' predictions of atomic physics.

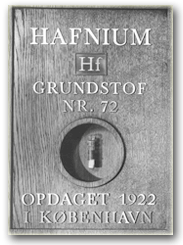

By the early 1920s Bohr was able to use his atomic theory to predict the properties of all chemical elements. Element number 72 posed a special problem, as experimentalists in England and France claimed to have found that the element belonged to the group in the periodic system called the rare earths, which was in contradiction to Bohr's theory.

Bohr was at first inclined to accept this result, but George Hevesy, a Hungarian physical chemist and close friend and colleague from 1912, set out, together with spectroscopist Dirk Coster from Holland, to investigate the matter experimentally at Bohr's institute.

By the end of 1922 they had established that the element satisfied the criteria set by Bohr's theory, something that Bohr was able to announce in the published version of his Nobel Prize Lecture. The new element received the name hafnium, which is Latin for Copenhagen.

Finn Aaserud, historian of science, director of the Niels Bohr Archive