Comet headed for Mars

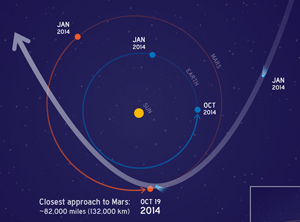

On Sunday evening, 19 October 2014 at 20:30, a comet will come closer to colliding with Mars than we have ever seen. The comet was discovered in January 2013 and was named Siding Spring. It initially appeared that it might be on a direct collision course with Mars, but it later became clear that Mars would just avoid being hit. Now we know that the comet will pass by Mars at a distance that is only a 1/3 of the distance between the Earth and the Moon at a speed of 200,000 km per hour on its way towards the Sun.

Artistic interpretation of the comet Siding Spring. The comet’s tail is a thin stream of gas with small amounts of microscopic dust that sprays out of the comet when it is heated up by the Sun. The tail can be several million kilometers long and therefore appears large in the sky, even if the comet is many millions of kilometers away. The nucleus of the comet is often just a few kilometers wide and is mostly comprised of ice. (NASA).

“Over the course of millions of years, the comet has fallen inward from the icy cold fringe of the solar system at an ever increasing speed. If it had hit Mars, it would have created a crater the size of greater Copenhagen and an explosion 10 million times more powerful than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Instead, it will now skim the Martian atmosphere and dust from the comet’s tail and small stones that are ripped off the surface of the comet during its long journey will burn up as shooting stars in the Martian atmosphere. The five satellites in orbit around Mars (Mars Odyssey (NASA, arrived in 2001), Mars Express (ESA, arrived in 2003/4), Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (NASA, arrived in 2006), MAVEN (NASA, arrived in 2014) and Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM, India, arrived in 2014) have been maneuvered into orbits that ensure that they are behind Mars during the 20 minutes the bombardment is expected to be the worst,” explains Uffe Gråe Jørgensen, associate professor and head of the research group Astrophysics and Planetary Science at the Niels Bohr Institute at the University of Copenhagen.

When we see a large comet in the sky, we immediately think of the beautiful tail. The tail is an immensely thin stream of gas with small amounts of microscopic dust that reflects sunlight. Because the tail can be millions of kilometers long, it appears large in the sky even if the comet is many million kilometers away. The nucleus of the comet is often just a few kilometers wide and is mainly made of ice. The tail is the gas and dust that sprays out of the comet when it is heated up by the Sun, like geysers that spray up from the ground when water runs over hot volcanic rocks underground and causes the water to boil up.

Comet pieces hitting the Earth

Every year, the Earth passes through the remains of many comet tails and the particles that hit the Earth’s atmosphere give rise to meteor showers like the Perseids in August. In June 1908, the Earth passed right through the centre of a small comet tail and the newspapers in Denmark wrote the day after that, “one wondered why it would not become dark yesterday night”. It was so bright over Denmark that you could sit outside and read a newspaper at midnight. The light was from the comet tail that the Earth was passing through, but no one knew at the time. A few hours later, a 50-meter chunk of comet collided with the Earth near the Tunguska River in Siberia, destroying 2000 square kilometers of forest.

The comet Siding Spring, discovered in January 2013, is currently racing towards Mars, where it will collide with the Martian atmosphere 19 October at 20:30 Danish time. It is more than 1000 times larger than the comet fragment that hit Tunguska in Siberia in 1908 and cleared more than 2000 square kilometers of forest. When the comet Siding Spring collides with the Martian atmosphere, it is expected that just the friction between the comet-atmosphere, called the coma in technical jargon, and the Martian atmosphere will cause the temperature in the Martian atmosphere to increase by 30 degrees. (NASA)

But the comet Siding-Spring, which will pass Mars on Sunday, is more than 1000 times larger than the Tunguska comet fragment from 1908 and it is expected that just the friction between the comet-atmosphere, called the coma in technical jargon, and the Martian atmosphere will cause the temperature in the Martian atmosphere to increase by 30 degrees.

Observing violent collisions

By a stroke of luck, an American satellite, MAVEN, has just entered into orbit around Mars. MAVEN is the acronym for Mars Atmosphere and Volatile EvolutioN, i.e. a satellite that is specifically designed to study changes in the Martian atmosphere and its composition. When designing MAVEN, the scientists had it in mind to study what happens in the Martian atmosphere when violent eruptions on the Sun cast large quantities of material through the solar system. But now MAVEN can provide detailed information about what happens when a comet collides with a planet’s atmosphere like what happened on Earth in 1908 and it will be to an even more severe degree on Mars on Sunday.

There are several other instruments on the surface of Mars ready to observe the impact, including the Mars rover Curiosity, which Danish researchers at the Niels Bohr Institute have instruments on board. There are also a number of telescopes around the world that will follow action from Earth. You need a telescope with a diameter of at least 20 cm in order to see the event directly, but from the surface of Mars, the comet will be nearly as bright as the full moon when it is at its closest approach.

On 12 November yet another historic comet event will take place when the lander Philae from the European Rosetta space probe is expected to land on the comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

Uffe Gråe Jørgensen, Associate Professor and leader of the research group Astrophysics and Planetary Science at the Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, 3532-5998, 6130-6640, uffegj@nbi.dk