Radio- and microwaves reveal true nature of dark galaxies in the early Universe

Utilizing multiple radio telescopes across the world, a team of astronomers from the Cosmic Dawn Center, Copenhagen, have discovered several galaxies in the early Universe that, due to massive amounts of dust, were hidden from our sight. The observations allowed the team to measure the temperature and thickness of the dust, demonstrating that this type of galaxies contributed significantly to the total star formation when the Universe was only 1/10 of its current age.

Measuring the rate at which stars are born in galaxies across cosmic time is one of the fundamental ways astronomers describe the properties and the evolution of galaxies.

Various methods are used to estimate this so-called star formation rate, typically depending on the light that is emitted from either the stars, or from matter that is illuminated by the stars.

Cosmic dust

However, the stars that are formed tend, in turn, to create dust — particles made of heavy elements such as carbon, silicon, oxygen, and iron. The dust appears as thick clouds in the space between the stars, possibly hiding the stars completely from our eyes.

This makes it difficult to get a census of the star formation rate especially in young, "starburst" galaxies, where the dust has not yet had the time to disperse far from the compact sites of star formation.

As the dust is heated by the stars, it begins to glow in long-wavelength, infrared light which, although invisible to the human eye, may be detected by telescopes designed to observe these wavelengths.

But for the most compact, dust-enshrouded starbursts, we only see the surface of the clouds. These galaxies are invisible not only at the "humanly perceivable", optical wavelengths, but also in the beginning of the infrared spectrum, utterly dark even to the Hubble Space Telescope.

Galaxies on the Radio

A team of astronomers — led by Shuowen Jin (靳硕文), Marie Curie postdoc fellow at the Cosmic Dawn Center, and including several other DAWNers — therefore decided to take a look at the early Universe at even longer wavelengths, using the radio/microwave antennae at two of the world's largest radio observatories, the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, and the Northern Extended Millimeter Array (NOEMA) in France.

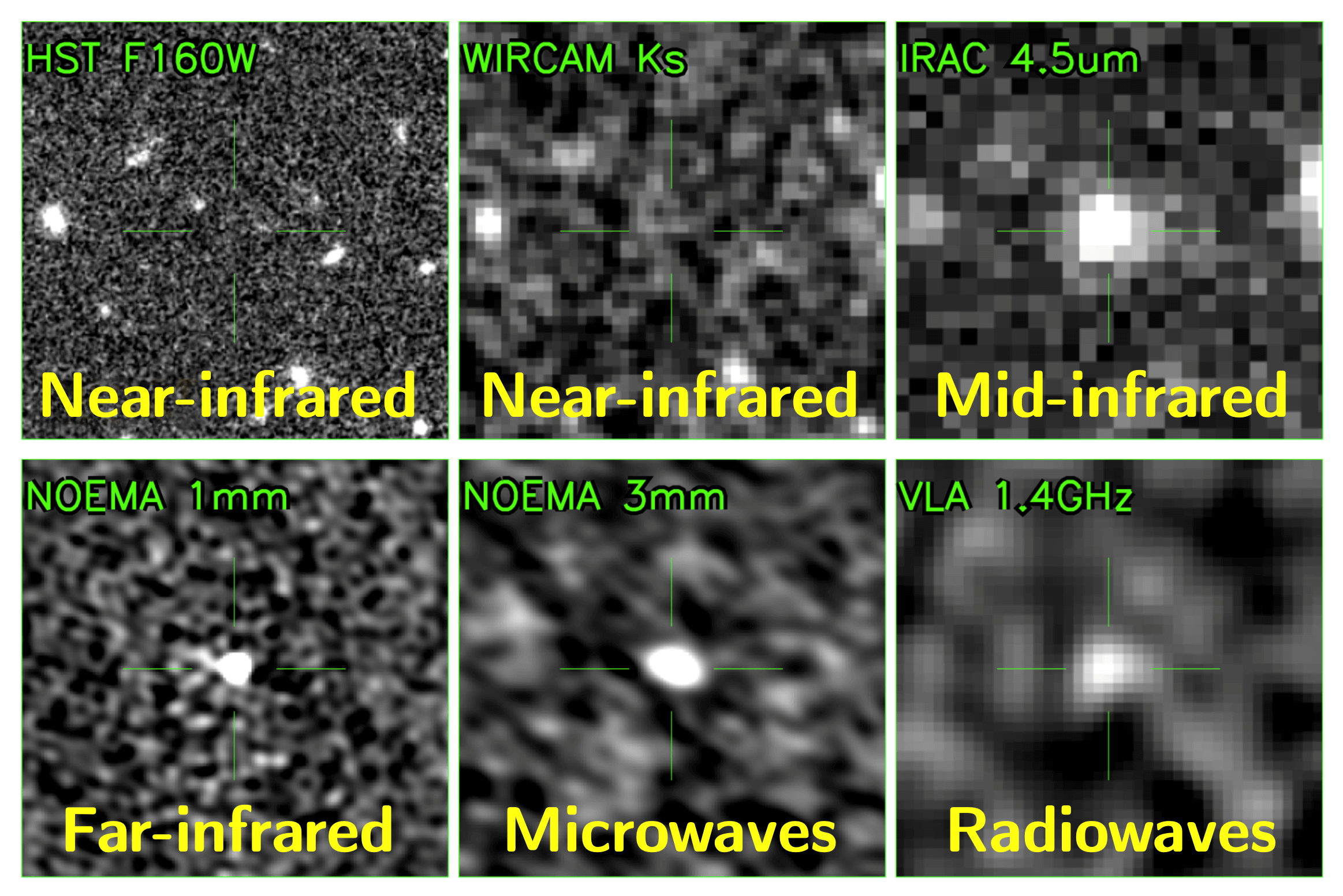

Six different views of the same galaxy (ID12646), seen less than a billion years after the Big Bang, at progressively longer wavelengths. The two first images show — or rather do not show — the galaxy in the near-infrared; the galaxy is completely invisible. Only when looking at the longer wavelengths is the galaxy revealed (credit: Shuowen Jin / Peter Laursen).

Together with observations of the same field on the sky acquired with other radio telescopes, Jin's observations revealed a population of compact starburst galaxies, cloaked in extremely thick dust clouds.

Piercing through the clouds

The radio- and microwave observations allowed the astronomers to measure the star formation rate and the temperature of the dust.

"In these epochs, 1–2 billion years after the Big Bang, galaxies like these contributed significantly to the total star formation rate of the Universe, but pass unnoticed in optical and near-infrared observations," says Shuowen Jin.

The study explains why these galaxies are so dark in optical and infrared: "Because the dust clouds are so thick and dense, optical and near-infrared light cannot travel through. Even the far-infrared light is partially absorbed," Shuowen Jin explains.

The observations reveal not only dust, but also monoxide molecules (CO), mixed within the clouds. The light emitted by CO can help astronomers probe another important quantity of galaxies, namely the mass of all the gas in the galaxy. However, one of the key results of the work of Jin and his collaborators is that the standard way of inferring gas masses from CO emission is erroneous:

The observed light is emitted from the surfaces of the dusty clouds. Typical models do not consider that light is blocked inside the clouds, changing its wavelength before it escapes. Taking this effect into account has rather drastic implications:

"Our model accounts for the fact that even the infrared light does not escape directly from the center of the dust clouds. This shows us that previous estimates of gas masses have been overestimated by a factor of 2–3 in compact, dusty, star-forming galaxies," Shuowen Jin explains.

The study has just been accepted for publication in Astronomy & Astrophysics. A preprint is available at arXiv:2206.10401.

Contact

Shuowen Jin, Extern postdoc

Email: shuowen.jin@gmail.com

Georgios Magdis, Postdoc

Email: georgios.magdis@nbi.ku.dk