Colliding neutron stars provide a new way to measure the expansion of the Universe

In recent years, astronomy has seen itself in a bit of crisis: Although we know that the Universe expands, and although we know approximately how fast, the two primary ways to measure this expansion do not agree. Now astrophysicists from the Niels Bohr Institute suggest a novel method which may help resolve this tension.

The Universe expands.

We’ve known this ever since Edwin Hubble and other astronomers, some 100 years ago, measured the velocities of a number of surrounding galaxies. The galaxies in the Universe are “carried” away from each other by this expansion, and therefore recedes from each other.

The greater the distance between two galaxies, the faster they move apart, and the precise rate of this movement is one of the most fundamental quantities in modern cosmology. The number that describes the expansion goes by the name “the Hubble constant”, appearing in multitude of different equations and models of the Universe and its constituents.

Hubble trouble

To understand the Universe we must therefore know the Hubble constant as precisely as possible. Several methods exist to measure it; methods that are mutually independent but luckily give almost the same result.

That is, almost…

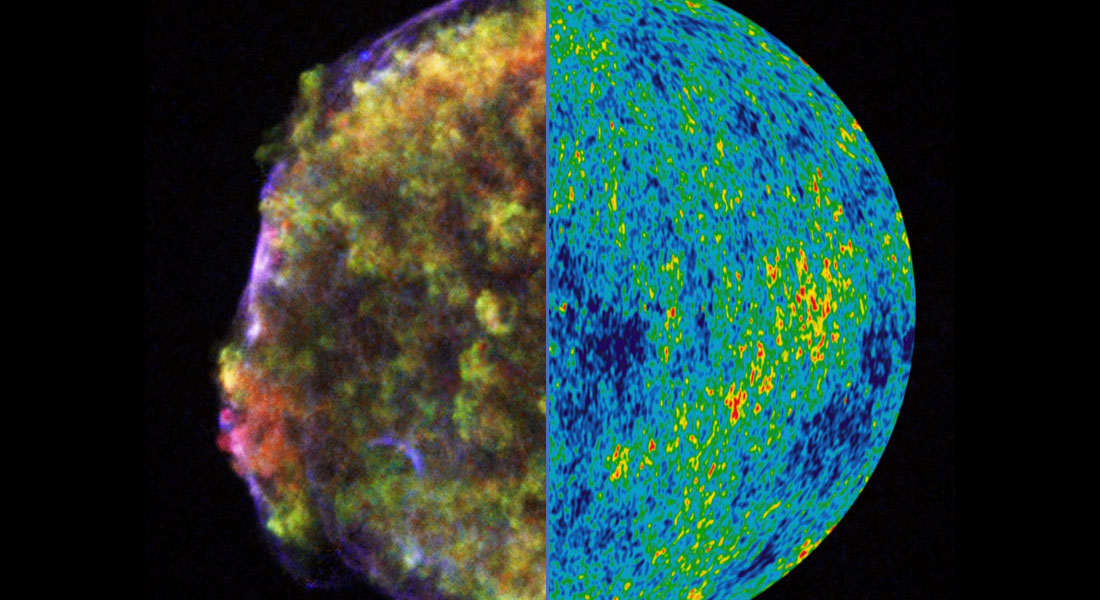

The intuitively easiest method to understand is, in principle, the same that Edwin Hubble and his colleagues used a century ago: Locate a bunch of galaxies, and measure their distances and speeds. In practise this is done by looking for galaxies with exploding stars, so-called supernovae. This method is complemented by another method that analyzes irregularities in the so-called cosmic background radiation; an ancient form of light dating back to shortly after the Big Bang.

The two methods — the supernova method and the background radiation method — always gave slightly different results. But any measurement comes with uncertainties, and a few years back the uncertainties were substantial enough that we could blame those for the disparity.

Nevertheless, as measurement techniques have improved, uncertainties have diminished, and we've now reached a point where we can state with a high degree of confidence that both cannot be correct.

The root of this “Hubble trouble” — whether it is unknown effects systematically biasing one of the results, or if it hints at new physics yet to be discovered — is currently one of astronomy’s hottest topics.

Crashing neutron stars may help with the answer

One of the greatest challenges lies in accurately determining the distances to galaxies. But in a new study, Albert Sneppen who is a PhD student in astrophysics at the Cosmic Dawn Center at the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen, proposes a novel method for measuring distances, thereby helping to settle the ongoing dispute.

“When two ultra-compact neutron stars — which in themselves are the remnants of supernovae — orbit each other and ultimately merge, they go off in a new explosion; a so-called kilonova,” Albert Sneppen explains. “We recently demonstrated how this explosion is remarkedly symmetric, and it turns out that this symmetry not only is beautiful, but also incredibly useful.”

Illustration of the two methods used to measure the expansion of the Universe: The left hemisphere shows the expanding remnant of the supernova discovered by Tycho Brahe in 1572, here observeret in X-rays (credit: NASA/CXC/Rutgers/J.Warren & J.Hughes et al.). On the right is a map of the cosmic background radiation from one half of the sky, observed in microwaves (credit: NASA/WMAP Science Team).

In a third study that has just been published, the prolific PhD student shows that kilonovae, despite their complexity, can be described by a single temperature. And it turns out that the symmetry and the simplicity of the kilonovae enable the astronomers to deduce exactly how much light they emit.

Comparing this luminosity with how much light reaches Earth, the researchers can calculate how far away the kilonova is. They have thereby obtained a novel, independent method to calculate the distance to galaxies containing kilonovae.

Darach Watson is an associate professor at the Cosmic Dawn Center and a co-author of the study. He explains: “Supernovae, which until now have been used to measure the distances of galaxies, don’t always emit the same amount of light. Moreover, they first require us to calibrate the distance using another type of stars, the so-called Cepheids, which in turn also must be calibrated. With kilonovae we can circumvent these complications that introduce uncertainties in the measurements.”

Confirms one of the two methods

To demonstrate its potential, the astrophysicists applied the method to a kilonova discovered in 2017. The result is a Hubble constant closer to the background radiation method, but whether the kilonova method can resolve the Hubble trouble, the researchers do not yet dare to state:

“We only have this one case study so far, and need many more examples before we can establish a robust result,” Albert Sneppen cautions. “But our method at least bypasses some known sources of uncertainty, and is a very »clean« system to study. It requires no calibration, no correction factor.”

Contact

- Article

- Sneppen et al. (2023): Measuring the Hubble constant with kilonovae using the Expanding Photosphere Method

- Cosmic Dawn Center

The Cosmic Dawn Center (DAWN) is a center of excellence for astronomy, supported by the Danish National Research Foundation. The center is dedicated to uncovering when and how the first galaxies, stars and black holes formed and evolved in the early Universe. DAWN is a collaboration between the Niels Bohr Institute at the University of Copenhagen, and at the National Space Institute at the Technical University of Denmark (DTU Space).