Development of the instruments

After first being invited to participate in a NASA mission and then being left out several times, it was finally decided that the Danish Mars Group would have instruments sent to Mars. And so began the great task of developing the instruments.

When it dawned on the researchers in the Danish Mars Group that it might still be possible to provide instruments for a future Mars mission, the group began to consider how they might actually build the instruments themselves.

Designed by "amateurs"

Should they – as had been the case with the first magnet experiments during NASA's Viking mission – leave the production of the instruments to a commercial enterprise?

Or should they seek the advice of – and possibly ally themselves with – local experts in Denmark (the Niels Bohr Institute's mechanical workshop, the electronics workshop and the Danish Space Research Institute's experienced experts) to make use of their expertise – but otherwise produce the instruments locally?

Whichever solution they chose, detailed ideas and requirements for the magnet instruments had to be drawn up and, in principle, everything was open and had to be invented and made from scratch.

Detailed requirements from NASAThe challenge was that no one in the Mars Group had any practical experience with space missions. In addition, this was not 'just' a mission where something would be sent into orbit around the Earth, but rather involved delivering a so-called 'space qualified flight hardware' for a 'deep space mission' with all of the requirements that come with such a situation.

They had to negotiate with NASA about the detailed requirements for the features of the instruments, both in terms of the scientifically relevant parameters such as the desired magnetic fields on the surface of the metal plates, but also, for example, the details of how the plates were to be mounted on the lander.

The formal documents describing this latter part are called 'interface control documents' and they define very precisely how the finished instruments should be mounted on the lander: Bolt hole geometry, orientation in relation to the camera, size and additional specifications for mounting bolts or rivets.

Another thing that was new to the group was that the materials could not be freely chosen. For example, with regard to adhesives, only certain special adhesives can be used for space missions, because of heavy demands due for low outgassing in a vacuum, temperature stability and also the thickness of the glue joint.

In a close collaboration between researchers in the Mars Group and the precision engineers at the Niels Bohr Institute's central workshop, they developed a set of permanent magnets, a so-called 'magnet array'.

But as the group carried out simulation experiments with various Mars analogue materials – and as the collaboration with NASA and took shape –new opportunities for supplementary instruments appeared ...

Three different magnet experiments

At the end of 1995 – about a year before Mars Pathfinder was to be launched – three different magnet experiments were under development at the Niels Bohr Institute.

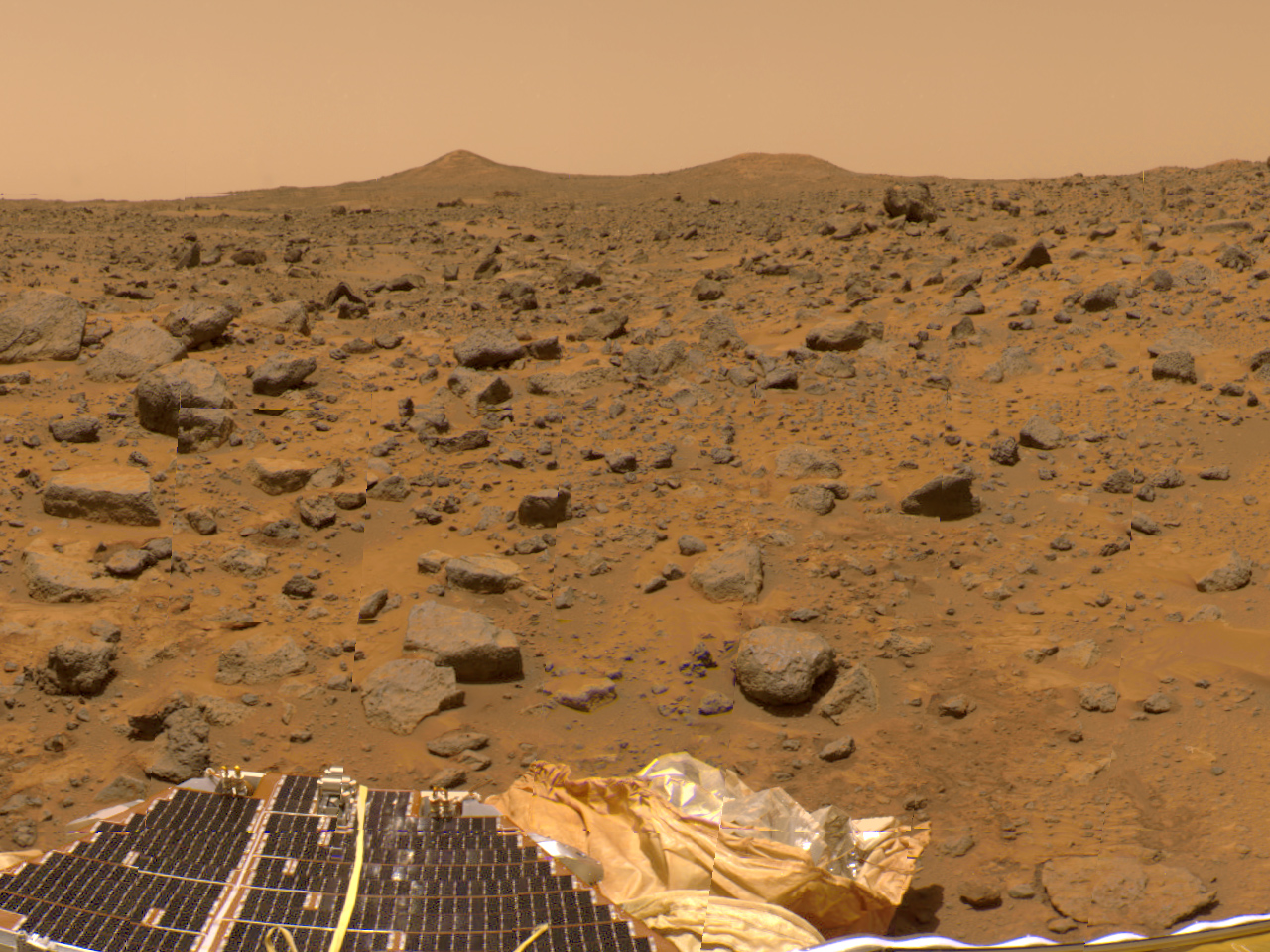

1. The small magnet from the camera's "tip-plate", which was observed using a special magnifier in the camera.

2. One of the two ramp magnets for studying the elemental composition of the most magnetic dust particles.

3: The 'magnet array' located closest to the camera.

4. The lower of the two 'magnet arrays' on the base frame of the lander. The captured dust particles form a pattern on the metal plates over the built-in magnets.

These images were taken on Mars in 1997.

First was the aforementioned 'magnet array' (figures 3 and 4), consisting of five different magnet configurations hidden in a neutral appearing metal plate. Second was a little instrument, the 'tip-plate magnet' (figure 1), for mounting close to the camera head to examine potential chain formation of the attracted particles.

Finally, development had also started on a series of ramp magnets (figure 2) to be mounted on the edge of the ramps that would bring the little rover, Sojourner, safely to the Martian surface.

The idea was that the ramp magnet would attract a thin film of the most magnetic dust particles from the air and they would then use the elemental analyser mounted on Sojourner until late in the mission to make an elemental analysis of the dust on this magnet.

The aim was to investigate whether the element titanium accompanied the element iron in the magnetic phase in the dust. If that were the case, then you could very probably reject the idea that water had played a major role during the formation of the dust. As Jens Martin Knudsen put it a bit bluntly: "If titanium follows iron in the magnetic phase in the dust, you can forget about water on Mars".

All these instruments were built at the Niels Bohr Institute and mounted on the Pathfinder lander and in December 1996 they were sent to Mars.

Calibrating the camera

The Mars Group, along with Peter Smith from the Lunar and Planetary Science Laboratory at the University of Arizona in the lead, also contributed to the extensive work of calibrating the camera ('Imager for Mars Pathfinder' or IMP).

Not only did this activity give the group members with their American colleagues, but the work also provided them with a thorough knowledge of the camera's features and the developed control software.

In addition, the participation meant that the Danish Mars Group was expanded with three additional physicists, Stubbe Faurschou Hviid, Haraldur Páll Gunnlaugsson (called Palle) and Walter Goetz.

Because of NASA's very tight budget for the mission, the associated scientists needed to be involved in all of the practical activities related to the mission on the surface of Mars.Stubbe Faurschou Hviid and Haraldur Páll Gunnlaugsson both travelled to Tucson, where they stayed for several months and participated both in the calibration of the camera and the development of the control software.

This was especially true in the planning of the recording of the image data and generating of the codes to be sent to Mars each morning to tell the mission's camera what it should do during the day.

In this way, it was possible for the Danish Mars Group to participate in parts of the mission that they never would have thought would be available to them.

With tears in their eyes

Mars Pathfinder was launched in 1996 and after a journey of seven months it landed on Mars on 4 July 1997. Jens Martin Knudsen experienced the moment with tears in his eyes from the front row at NASA.

"11 minutes after the landing a single beep sounded from the control centre. The message from the probe that everything was as it should be," he told Politiken.

When it became clear that everything was working and that the landing had been successful, he called home to his parents in Haurum. "When we had talked for about 45 seconds, my father said the last sentence I heard him say alive. It was: Let us stop. It is too expensive," said Jens Martin Knudsen.